I don’t divide architecture, landscape and gardening; to me they are one.

~ Luis Barragan

LANDSCAPE VISION

The Owners’ desire for a truly integrated Architecture and Landscape determined the working relationship among the Owners, mills studio, and Landscape Architect. After exploring an arrangement of contracting directly with a Landscape Architect the Owners decided to task mills studio with the responsibility for a landscape design that would align with the Owner’s sustainability and lifestyle requirements, along with the understanding at the urging of mills studio, that mills studio would consult with Lisa Gimmy Landscape Architects (LGLA) in the landscape design process. mills studio believed that it could best initiate a vision of the landscape design that would properly integrate with the architectural agenda and the Owners’ requirements and that LGLA could uniquely help clarify, reinforce, and implement that vision. The landscape design vision requires a critical analysis and examination with both an intellectual and technical expertise to make the vision appropriately tangible. LGLA’s belief in landscape as a cultural endeavor, ability to balance intellectual curiosity with technical competence, and direct experience working with modernist design, such as Richard Neutra’s work, makes LGLA perfectly suited to help the Owner and mills studio implement its vision for the DTS Project House.

LGLA, Kun II (Richard Neutra 1957), Los Angeles, California

LGLA, Architect’s Garden, Bel Air, California

Lisa Gimmy Landscape Architects – Culver City, California

OWNERS DIRECTIVE

The five specific directives:

1. Architectural elements and Landscape elements must provide privacy from neighbors.

2. There must be a path that gets you from the ground level of the house to the walking trails accessed at the bottom of the property.

3. The lower part of the property should contain destinations, such as a “writer’s cottage.”

4. The landscape development should accentuate the size of the property beyond the footprint of the house.

5. The existing elements of the landscape, such as cactus, should be incorporated, accentuated, and extended to create a landscape using minimal water and requiring as little maintenance as possible.

mills studio STATEMENT

Like Architecture, Landscapes are generated from the intersection and reconciliation of universals and particulars. Landscape solutions answer the site’s environmental challenges, the client’s pragmatic directives, and the Landscape Architect’s agenda of values, theories, and methods. mills studio’s methods begin with a detailed and systematic “ecological inventory” of the site’s natural features and processes as pioneered by Ian McHarg. Although this inventory provides the complete scientific picture of the site’s physical context, data and a scientific understanding of the site do not provide criteria for making aesthetic decisions. Similar to many practitioners addressingthe longstanding debate of science versus art in Landscape Design, James Corner of Field Operations points out the “dichotomous split between the environmentalists and the artists …” and goes on to state “there is nothing natural about the landscape: even though landscape invokes nature and engages natural processes over time, it is first a cultural construct, a product of the imagination.” Landscape is most significant when this “split” is reconciled with science focusing the imagination and the imagination raising science to an aesthetic experience.

Construction necessarily upsets and alters a site’s existing man-made or natural character. The Architecture and Landscape and their interaction will help determine if that intrusion ultimately spoils, repairs, or enriches the site’s existing character or in some cases gives character to a characterless site. The Landscape and its interaction with the Architecture should help perfect the site. Perfecting the site means to accentuate and clarify the sites character while simultaneously using the site to accentuate and clarify the Architecture. A site’s character should be defined in broad terms including its physical, intellectual, and spiritual characteristics – its full context. The interaction of the Architecture and Landscape has the opportunity and responsibility to make the site’s character perceptible. Perfecting the site is also achieved when the architecture and landscape are so physically and conceptually intertwined that neither is imaginable without the other. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater and Mies Van de Rohe’s Farnsworth House manifest such perfection. As these two projects make clear though, perfecting the site neither implies a single approach nor a particular aesthetic.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s “Fallingwater” built in 1936, located in Bear Run, Pennsylvania

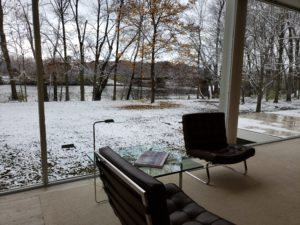

Mies Van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House built in 1951, located in Plano, Illinois

Landscape Design has the opportunity to address both the strictly “Landscape” aspects of topography, vegetation, and the micro-environment and the more expansive macro aspects of site like culture, politics, and environmentalism. The landscape often is the physical mediator between the building and the larger physical world, but also has the opportunity to mediate between “nature and culture”. As James Corner of Field Operations states, “as the great mediator between nature and culture, landscape architecture has a profound role to play in the reconstitution of meaning and value in our relations with the earth.” mills studio takes a very expansive view toward what constitutes “our relations with the earth,” from the physical to the spiritual connections.

One’s view of our ideal “relations with the earth” helps determine one’s approach to landscape design and the interaction between Architecture and Landscape. Significant Architecture expresses a clear viewpoint of man’s ideal relation to the earth. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater and Mies Van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House are useful examples of how serious architects use building and landscape interaction to express very different viewpoints of man’s ideal relation to the earth. These two houses express two poles of how building and landscape interact: melding and opposing. Fallingwater and the Farnsworth House model both visually and experientially Wright’s idea of architecture and landscape melding and Mies’ idea of architecture and landscape opposing. What makes these two examples so powerful is that the physical melding and opposing is a manifestation of each architect’s worldview and thus man’s place in the order of things.

Much thinking about the relationship between humans and nature and how that manifests itself in Architecture and Landscape is related to two consistent images of paradise: Eden and Jerusalem. At one pole, paradise is a garden for a completely free individual living in nature, and at the other pole paradise is a city where man is a conforming member of a community. In simple terms, Architecture is about the city, Landscape about the garden, and their interaction the resolution of these two poles. Architecture and Landscape can reconcile man’s simultaneous need for both liberty and rootedness and in so doing create necessary experiences of both exhilaration and endurance.

Landscapes necessarily take a position on environmentalism. Like in many other social movements, many environmentalists have offered science as a basis for determining ethical and moral courses of actions. But science cannot substitute for values – ethics cannot be grounded in science. Decisions regarding if we should preserve nature (environmentalism) or manage nature (conservation) are based upon values and our belief of why man inhabits the earth. Science can provide data and tell us the scientific results of our actions, but only values can tell us the right actions. A responsible environmentalism would celebrate nature and would combine science and values to express that man’s life is simultaneously intimately connected to the earth and that man holds a privileged position on the earth.

Landscapes can often be divided into chiefly for contemplation or for engagement. Some Landscapes are offered for gazing upon and others for the interaction of humans with their environment. The most dynamic Landscapes fulfill both of these roles providing both optical and spatial experiences. The combination of these distinct experiences make Architecture and Landscape more dynamic because the combination addresses both the macro and micro which the human being’s life must also address in order to fulfill the need for both the conceptual and the emotional.

The Architecture / Landscape interaction confronts the relationship between inside and outside. Sometimes this connection is purely physical and is sometimes more metaphorical. Again, the experience of the interaction is more dynamic when the design integrates both the physical and the metaphorical. The connections become more complicated and more interesting on a hillside site where most of the building may be divorced physically from the ground. There is little or no direct indoor-outdoor experience in the Mid-century sense of walking from inside to outside. Thus the “landscape” must be expanded to rise above the ground if landscape is to be an integral part of living on a hillside. The “landscape” must function as an optical experience and not just something to occupy. Nature is often sensed more intensely when viewed through an architectural lens because nature is only made significant with man’s occupation.

Landscape can fulfill and express multiple intentions: serve programmatic requirements; expose natural phenomena; reflect on man’s place on earth; spur insight on man’s relationship to nature; and provide aesthetic experiences of delight. A broader definition of what constitutes Landscape and the interaction between Architecture and Landscape can expand the goals of Landscape into areas such as Land Art. The more of these goals a single Landscape attempts to meet the more significance a Landscape can achieve. It is ironic that often this significance is achieved through an aesthetic of temporality. Unlike architecture’s inherent permanence, major portions of Landscape are inherently ephemeral. In the most significant buildings a constantly evolving Landscape combines with a fully formed Architecture to give meaning to our experiences of each.

The outside is always an inside.

~ Le Corbusier