Tip the world over and everything loose will land in Los Angeles.

~ Frank Lloyd Wright

Design Context

Architecture originates generally from its client’s direction and its architect’s agenda and then is made specific by its physical, historic, and cultural context. The DTS Project House derives its particular architecture from mills studio’s and the Owner’s modern aesthetic sensibilities; the physical requirements and opportunities of codes and site; and the rich historic and cultural development of the immediate neighborhood, Hollywoodland, Los Angeles, and Southern California.

Client

The starting point for an architectural implementation is the Client’s general and specific requirements and their aesthetic sensibilities. The DTS Project House design has to respond to the Client’s desire to show that sustainability can be glamorous and can be married to high design; a desire to integrate innovative technologies; and specific requirements like an extra long parking space and infrastructure for charity events. The Client has completed a series of previous building projects that tangibly showed mills studio the Client’s affinity for a Modern aesthetic and what can be loosely labeled “Hollywood Glamour”. The very active participation of the Client and a continuous dialog between mills studio and Client in the design and building process greatly inform the final architectural expression.

mills studio

mills studio brings a consistent architectural agenda to each project that addresses the universal purposes of architecture that are not relative to other project contexts. This agenda starts with the intention to express the importance of the institution housed and how that institution supports the societal structure that is necessary for the stability of the city. Among the other aspects of the architectural agenda is the hebraic-romantic tradition that how something is made is more important than what it looks like and what it looks like should be a result of what it is made of. The agenda is based upon a belief that Architecture is a conservative art that works best when it is conserving and not over turning. The architectural agenda does not prescribe a specific aesthetic or a particular architectural solution, but gives a larger universal purpose to the particulars prescribed by the other aspects of a project’s context.

Codes and Ordinances

Building Codes and local Ordinances both drive general design approaches and specific design details. The local Hillside Ordinance sets the parameters for the building height at the street and as it steps down the hill, sets the number of on site parking spaces, defines the allowable square footage, and helps determine portion of building to be built above and below grade. The existing geological conditions and the required structural design for resistance to earthquakes affects the structure design and material choices. The California Green Building Code and its and Title 24 requirements affect general design approaches and specific design details and product choices. LID / SUSMP requirements affect overall site planning and landscape / hardscape details. Public Works requirements for Highway Dedication and street widening affect building access and building placement. LEED requirements necessary for Platinum Certification affect everything from general design approach to material and product choices. Unfortunately many of these code requirements compete with one another instead of working in concert and often focus on specific prescriptions instead of allowing solutions that actually address a code’s intent.

Location

The DTS Project House’s physical and cultural location simultaneously within Southern California, the City of Los Angeles, Hollywood, the Hollywood Hills, Beachwood Canyon, Hollywoodland, and on Creston Drive, gives the house both a rural and urban context of multiple scales. The physical and cultural contexts sometimes align and sometimes provide competing interests to resolve. The local, city, and regional contexts also sometimes align and sometimes provide competing interests to resolve. These multiple scales and competing interests affect everything from general design approaches to specific design elements to construction techniques.

Site

The hillside site’s physical parameters cannot be ignored and provide design opportunities. Its physical location and access affect what can be delivered to the building site and how it has to be delivered. The geology of the site provides particular design parameters and leads directly to the gabion design element. The southern orientation that follows the slope of the hill provides a roof slope with optimal solar orientation and affects shading and glazing treatments. The site’s temperate microclimate allows for a solar chimney to help cool the house without mechanical means. The slope of the public street allows for entry to the site at multiple elevations. The severe slope, southern exposure, and lack of soft edges give the site a certain toughness that calls out for bold gestures and materials and a landscape that can thrive and age in a rather harsh environment.

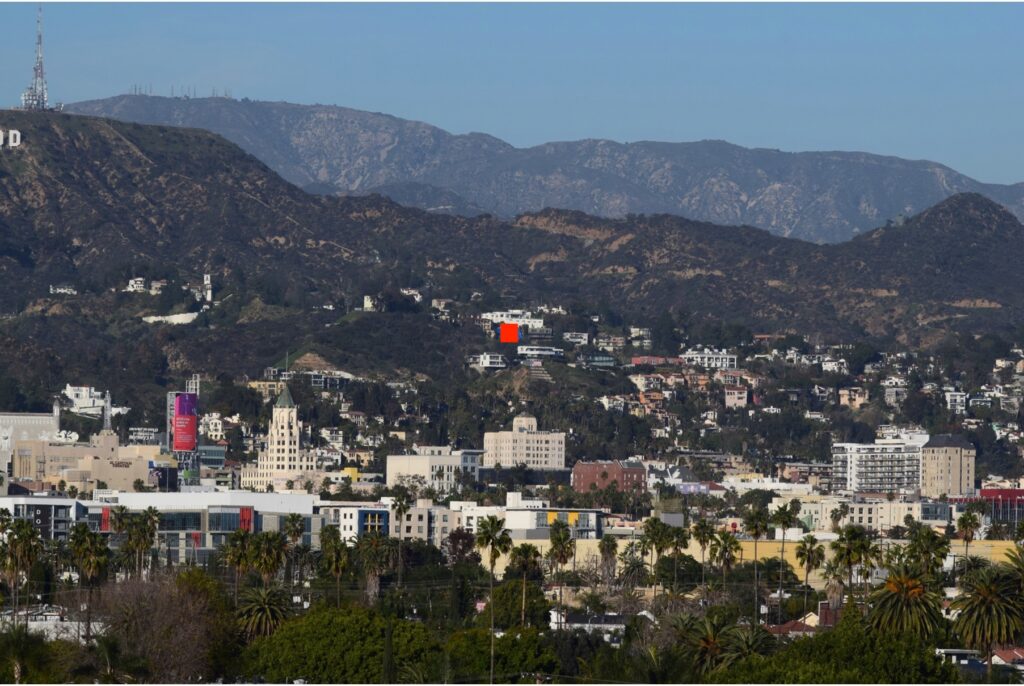

Views To and From

The DTS Project House site occupies a position in the city that simultaneously provides panoramic views of the city and views of itself from the city – it can see and be seen. The site’s elevation and position in the hills affords near views of both the surrounding hills and the heart of Hollywood and distant views of downtown Los Angeles and the Pacific Ocean. The house’s orientation, room positions in plan and elevation, and glazing design are a direct response to opening the house to the stunning daytime and nighttime views. The design has to balance a strong desire to capture the views with a desire for privacy from neighbors and a desire to appropriately address the site’s climatic orientation.

The views of the property from both near and far make the DTS Project House part of a larger physical and metaphorical context. Because of its position relative to the Hollywood Sign, the project is seen from essentially any where in the city that you can see the Hollywood Sign. This provides an opportunity to make a visual and cultural connection to landmarks like Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Thinking about how the project presents itself visually to the city affects thinking about an Iconic roof shape, a profile against the hillside, and nighttime lighting. Attempting to make a cultural connection to the city hopefully inspires the design to live up to the innovation and excellence of the architects and artists building and creating in the city.

Neighbors

Living in the hills is often a balance of competing interests: desire for physical and psychological seclusion while simultaneously being part of a neighborhood with neighbors. The proximity of neighbors above and below and the closeness of neighbors on the immediate sides of the property makes privacy screening a concern that leads to specific approaches to positioning on the site in plan and elevation, positioning of elements like the pool, and landscaping, and leads to specific architectural elements like rock filled gabions and automated screening. The design addresses a desire to both physically and psychologically block views of the neighbors and an ability to alternatively open up or stay hidden from neighbors as desired and as daytime turns into nighttime.

Environmental

The DTS Project House’s location at the top of the hills gives it its own microclimate that is influenced by both maritime and interior air. Its position relative to the ocean and almost constant air movement makes it even more temperate than surrounding areas. This translates into temperatures as much as ten degrees less than surrounding areas during the hottest summer months and less need for heating during the winter months. Its temperate climate and influence of ocean air make a wide variety of plant life possible, from extensive existing cactus to widespread citrus. The unobstructed southern exposure aligns with the views toward the south to the ocean. The southern exposure also aligns with the downslope of the hill with the optimal angle of solar southern exposure closely matching the angle of the south sloping hillside. The usual yearly rainfall is very minimal which makes drought tolerant pants like the existing cactus optimal, but rain events in the hills are an opportunity to creatively and artistically get water from the top to the bottom of the hill in a way that combined with strategic landscaping prevents erosion and runoff. The DTS Project House attempts to welcome rain to the hills where it is often less than welcome.

Architecture gives a specific meaning to phenomena of nature and the elements in the same way that it gives a structure to human institutions, relations, and behavior.

~ Juhani Pallasmaa

Hollywoodland

Hollywoodland is the housing development commenced in 1923 in the upper part of Beachwood Canyon. A group that included Los Angeles Times publisher Harry Chandler, West Hollywood’s founder General M.H. Sherman and the real estate mogul Sidney Woodruff developed the area. The development was made famous by the Hollywoodland Sign constructed as advertising. The Los Angeles Times announced the new development, “as one of the most attractive residential sections of the City of Los Angeles”, and described it as a Mediterranean Riviera in the Hollywood Hills between Lake Hollywood and Griffith Park.

The original architecture and landscaping of Hollywoodland looked to varied sources in Europe for its inspiration, including France, Italy, and Spain with even the turreted castles of Germany recreated and still standing in the Hollywood Hills. The historic granite walls built from stone blasted out of the hillsides to create flat building pads and drivable roads are still a signature aspect of the neighborhood. The erection of the Hollywoodland sign in 1923 expressed that Hollywood was now not just a physical location but an “industry, a lifestyle and increasingly, an aspiration.

Neighborhood

The site’s immediate neighborhood has a tradition of Modern Architecture and experimental structures. Richard Neutra’s Mosk House of 1933 and John Lautner’s Williams House of 1952 and Zahn House of 1957 are examples of Modern Architecture by two of its most celebrated practitioners. John Lautner also completed an addition to the Beachwood Market in 1954 and combined his modern tradition with the Norman inspired castle, Wolf’s Lair originally built in 1928. Architect Bernard Judge may have built the neighborhood’s most experimental structure beginning the construction of his Geodesic Dome in 1960 and completing it in 1962. The goal was similar to other architects and programs of the day: develop a construction system for economical housing with the use of the most current technology. Judge called his Hollywood Hills home the “Triponent House” as an expression of what he though were the three elements that made up the experimental structure: the envelope, the utility core, and the interior spaces. The envelope was a mylar and photo-electric cell covered 50’ diameter dome. All of the utilities such as the kitchen and bathrooms and the mechanical and electrical systems were placed in a prefabricated utility core. The interior spaces were an open framework for individual Owners to divide and design for themselves. Judge was awarded a patent for his innovative structural system and the geodesic framework has been moved to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. What new houses were built in the 70’s and 80’s rarely exceeded generic boxes, sometimes with hints of mid century modern architecture. A nostalgia for the original styles of the past, a growing interest in preservation, and the passage of progressively more restrictive codes and planning requirements were among the factors that discouraged architectural innovation. Architects Mark Angelil and Sarah Grahm’s own house of 1993 and Francois Perrin and Yves Lefay’s multistory house of 2012 are two examples of attempts to reignite the neighborhood’s tradition of architectural innovation.

Hollywood

Hollywood’s cultural and architectural histories inform the architecture of the DTS Project House. Hollywood was incorporated as a municipality in 1903 and officially became a part of the City of Los Angeles in 1910. Hollywood’s existence is dedicated to literally producing the dramatic, which has both made it a company town and a worldwide presence – both a local and global scale. From nearly the beginning Hollywood has been more than a physical city; the name Hollywood conjures a lifestyle and an aspiration that has attracted both companies and individuals since the beginning of the twentieth century. The Hollywood Hills has been an integral part of that lifestyle and aspiration that continues to attract tourists from around the globe.

One of the buildings that best captures the “drama” of Hollywood is the firm Welton Becket’s 13 story Capital Records Building of 1956. It was one of the world’s first circular highrises and many thought that the combination of its circular, wide awnings projecting at each floor and the tall spike projecting through the roof, alluded to a stack of records sitting on a turntable. Whether true or not, the architecture was used to brand the company, especially as the first on the west coast. The 1985 Hollywood Regional Library by Frank Gehry was a fresh take on what a library should feel like, a dark, musty formal place or as Gehry proposed, an informal, light filled space connected to the California sunshine. One of the newest architectural additions to Hollywood, Morphosis’ 2013 Emerson College, loosely mirrors the architectural concept of the DTS Project House: a set of “precious” inner glass volumes protected by a “tough” outer skin.

Los Angeles Architecture / Architects

Los Angeles has always attracted innovative architects building innovative architecture. Both the climate and the still enduring western spirit of adventure have attracted the clients and architects necessary to create architecture. Frank Lloyd Wright’s first project in Los Angeles was the 1921 Hollyhock House for Aline Barnsdall and he went on to complete several other LA projects including three textile block houses, with the Ennis Brown House of 1924 chiefly among them. An association with Frank Lloyd Wright was among the reasons European émigrés Rudolph Schlinder and Richard Neutra set up practice in Los Angeles. Rudolph Schlinder’s 1922 house for his own family, the Kings Road House, is the best example of Schlinder’s ideas about the modern family and building in the Southern California climate. Richard Neutra’s hillside Lovell “Health” House of 1929 was one of the first steel framed houses which allowed for a much more generous use of glazing letting in the Southern Californian sunshine. Neutra and his client, Dr. Lovell made a direct connection between a healthy well-being and natural light and this modernist idea is still influencing architecture today. Neutra’s VDL House of 1932 was built as a showcase of modern planning concepts, materials, and technology and in this sense is a model for the intentions of the DTS Project House.

The 1940’s saw the Case Study House Program initiated by Art and Architecture Magazine publisher John Entenza to inspire architects to show how modern building materials and prefabrication could economically meet the housing needs of returning GI’s and a growing population. Pierre Koenig’s Case Study Houses 21 and 22 are among the best examples of completed Case Study Houses and architectural photographer Julius Shulman’s photographs, especially of CSH 22, the Stahl House, spread the ideas and results of the Case Study House program around the world. Although not known primarily as Architects, Charles and Ray Eames designed CSH #8 in 1948 as an exemplar of architecture as the assemblage of prefabricated modern components. John Lautner, another apprentice of Frank Lloyd Wright, practiced in Los Angeles for more than 50 years creating the Goggie Style in his early career and went on to design many Los Angeles architectural icons such as the 1960 Malin House, 1956-1976 “Silvertop” House, 1962, 1972 Sheets-Goldstein House, and 1958 Garcia House that addressed hillside site conditions with advanced technological means and iconic roof defining shapes.

Both as an architect and as a founder of the Southern California School of Architecture (SCI-Arc) in 1972, Ray Kappe has had as much influence on Los Angeles architecture as anyone. His own 1967 hillside house is described by many as the iconic house in los angels and SCI-Arc has been among the world leaders in modern architectural education. Frank Gehry built his own house in 1978, and helped announce a new attitude toward architectural expression practiced by architects such as Thom Mayne of Morphosis, Eric Owen Moss, and other architects loosely labeled the “Los Angeles School.” Eric Owen Moss’ Conjunctive Points projects in Culver City, Morphosis’ Caltrans Building, and Gehry’s Disney Hall are all expressions of an architecture informed by 1960’s activism, architecture as revolution and disruption, and architecture as an expression of the messiness of modern life and urban conditions.

Southern California Architecture / Architects

Los Angeles’ history of innovative architects and architecture extends to all of Southern California. Charles and Henry Green’s Pasadena Gamble House of 1908-1909 is the perfect example of crafted architecture with its expressed structure and construction as “decoration” and outdoor living including sleeping porches. Most of the master modernists practicing in Los Angeles completed projects throughout Southern California. Rudolph Schindler completed the Lovell Beach House in 1926 in Newport Beach. Commissioned by the same client for Neutra’s Lovell Health House, Schindler addressed the client’s beliefs in connections between health and architectural design, such as natural air conditioning, and built a house of unadorned concrete using innovative structural frames to raise the building up off the ground to capture views and breezes.

Many Los Angeles architects have also completed projects in Palm Springs including Richard Neutra and John Lautner. Richard Neutra’s Kaufman House (same Kaufman as commissioned Fallingwater) of 1946 and Miller House of 1936 express the lightness and transparency of the so called International Style in a desert setting with an appropriate desert landscape. John Lautner completed the hillside Elrod House in 1968 and the Bob Hope House in 1973 and the Desert Hot Springs Motel in1947. Architects like Donald Wexler, E. Stewart Williams, and Albert Frey worked more exclusively in the Palm Springs area translating modernism to a desert context. Donald Wexler’s steel houses of the 1960’s with their butterfly roofs were studies in the artistic, economical assemblage of prefabricated steel parts. Albert Frey’s own House II of 1964, is a study in contrast: anchoring a lightweight modernist, man-made transparent box to a natural multi-ton boulder growing out of a rugged hillside.

Louis Kahn’s Salk Institute of 1963 in LaJolla is a masterpiece of twentieth century architecture and expresses how unadorned materials like concrete and wood can be made to possess the qualities of a temple. The Luis Barragan influenced central plaza dissolves into the western sky and Pacific Ocean in way that makes it one of architecture’s great spaces. Also in LaJolla, Williams and Tsien’s 1995 Neuroscience Institute carves a multiple level plaza into the earth and wraps the plaza with three low sand blasted concrete buildings forming what the architects call a “monastery for scientists.”

Southern California Art / Artists

Two aspects of Southern California life, light and space, inspire the name for the influential art movement of the same name. The artists of the1960’s Light and Space Movement aimed to make the viewer’s sensory experience of Light and Space the theme of their mostly three-dimensional works and installations. They owe their minimal geometric abstract qualities to artists like John McLaughlin and their technological basis to the widespread engineering and aerospace industries of Southern California. Many of the sparest works use just natural and or artificial light and others combine light with industrial materials like glass, resin, and acrylics to create spatial experiences often amplified by their architectural contexts. Among the original Light and Space artists, each with their specific focus, are James Turrell, Robert Irwin, Peter Alexander, Larry Bell, Doug Wheeler, John McCracken, Mary Corse, and Helen Pashgian. Many current artists, like Philip K. Smith III, Landscape Architects, like Andrea Cochrane are continuing the traditions and investigations of the California Light and Space Movement.

The strong connection between art and technology in Southern California is personified in the Art and Technology Program at LACMA from 1967 to 1971. The curator Maurice Tuchman pared artists with aerospace, scientific, and entertainment corporations to collaborate on artworks. Some collaborations did not result in completed artworks, such as James Turrell and Robert Irwin’s collaboration with the Garrett Corporation, and others produced artworks exhibited at the 1970 World Exhibition in Osaka, Japan and LACMA in 1971. Artists like Claus Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, Richard Serra, Tony Smith, and Andy Warhol did realize projects.

Maker Culture

Maker Culture is an extension of DIY culture that stresses technology as a tool of personal growth and liberation. Maker Culture grew out of a California design ethos, what Justin McQuirk has labeled “Designed in California”, commencing in the 1960’s. This “designed in California” ethos stresses applications of technology and intersections between traditionally separate domains. Stuart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog, the personal computer (especially Apple), and amazon.com, are among the manifestations of Makers belief that tools, in the broadest definition of tool, should be readily available and accessible to individuals to use – often to use in ways never foreseen or intended by their creators. Makers treat networking as a tool that allows them to share in the experience, skills, and knowledge of the community – a version of the “wisdom of the crowd.” The appeal and usefulness of Customer Reviews from sites like Amazon to Yelp, is an expression of the attitude that peers offer as much useful knowledge as so called experts. This emphasis on communal input has led to knowledge sharing platforms such as Wikipedia, crowd funding platforms such as Kick Starter, and shared collaboration platforms like cloud computing. Cloud computing has converged with sensor and embedded technologies to make the Internet of Things (IoT) a reality.

Maker Culture embraces an attitude of open sourcing where providing the user access to design specifications provides the user the ability to tinker with, “improve”, and make a design useful for alternative purposes. Elon Musk and Tesla embodied this attitude when they made their patents “open source” and thus available to everyone, including competitors. The success of the Apple iPhone and App Store is due to the fact that any individual has access to the necessary information that provides the ability to code an app that can work on an iOS device and be made available to the public. Everyone is now a “developer.”

Maker Culture encompasses an apparent contradiction that resolves in interesting ways: stressing self-reliance and simultaneously the power of collaboration and shared knowledge. Burning Man, the 33 year old annual “experiment in community and art” in the Nevada desert, which culminates in the burning of a wooden effigy, the “Man”, is a real world embodiment of Maker Culture values with both “radical self-reliance” and “communal effort” among its ten principals. At the same time Maker Culture values the use of technology, especially software, Maker Culture is also an attempt to reignite the artisan spirit. The DeYoung Museum, not coincidentally in San Francisco, serves as a model that is simultaneously a crafted building made up of computer fabricated copper panels based upon algorithms – one can be a craftsman with digital fabrication as your tool.

Maker Culture stresses learning by doing which leads to a design process of prototyping, editing, and gaining knowledge from making successive iterations of an idea. Makers do not feel the need to wait for the perfect design, product, or process, before making it available for public consumption. Make magazine first published in 2005 and in 2006 published The Maker’s Bill of Rights providing tangible manifestations of the Maker Culture ethos and can best be summarized in the simple tenants: “Power from USB is good: power from proprietary power adapters is bad” and “Screws better than glues.”

If you’re inclined to dismiss L.A. as a place of unrelenting vapidity and generic 1980s architecture then you’re doing yourself and L.A. a huge disservice, and you’re just not looking hard enough.

~ Moby